Rural healthcare, COVID-19 and making sure hospitals are ‘still standing’ after pandemic

More than 120 rural hospitals have closed in the last 10 years with hundreds more at risk, experts say

By Medline Newsroom Staff | June 24, 2020

One in five Americans – or nearly 60 million people – call rural America home. While images of rolling hills dotted with barns and silos may come to mind, healthcare leaders serving these communities say today’s picture of the rural experience is quite different and diverse.

Oftentimes, they are battling some of the same concerns as their urban counterparts like poverty, higher acuity patients, and now coronavirus – while also fighting for funding to stay alive. In fact, the National Rural Health Association (NRHA) says more than 120 rural hospitals have closed in the last 10 years, with more than 450 additional facilities vulnerable to closure.

With services and staff already stretched thin, rural communities are bracing for how the pandemic will take hold of them emotionally, physically and financially.

The Medline Newsroom spoke to rural healthcare leaders about COIVD-19 and how this crisis is forcing a deeper look at recovery, relevance and reality when it comes to delivering high quality care.

Chris Albertson

Chris Albertson

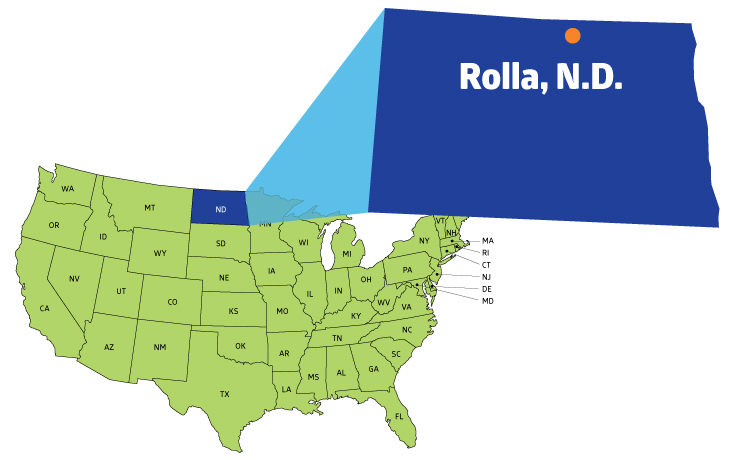

Presentation Medical Center, President and CEO

Rolla, N.D.

Pat Schou

Pat Schou

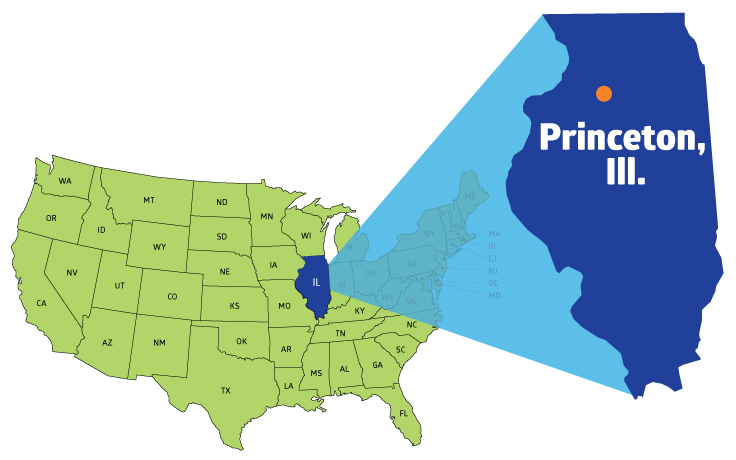

Illinois Critical Access Hospital Network, Executive Director

National Rural Health Association, President

Princeton, Ill.

Rex Walk

Rex Walk

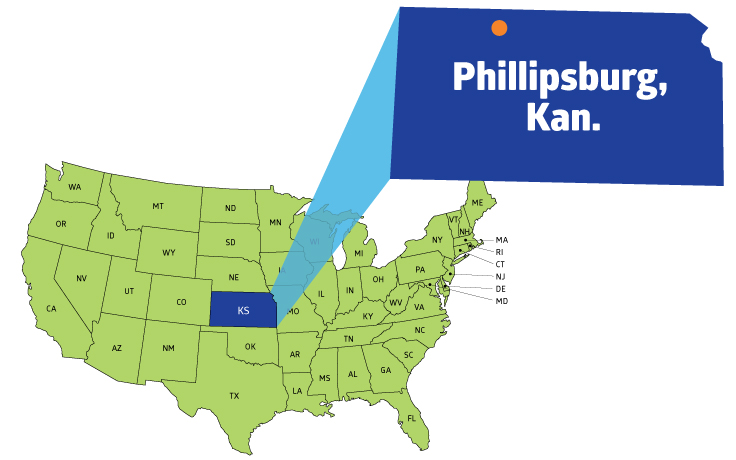

Phillips County Hospital, CEO

Phillipsburg, Kan.

Newsroom: Tell us about your role, your hospital and the community you serve.

Chris Albertson, Presentation Medical Center, President and CEO: I’ve been in my current role for a little over two years but now in my 19th straight year with Presentation Medical Center. I started as a respiratory therapy student, came on staff, got my MBA and then moved up through the organization. We’re a critical access hospital with 25 beds. We have swing bed services and ramped those up prior to COVID-19. We also have an attached, provider-based rural health clinic and offer podiatry, OB/GYN and general surgery. Rolette County here in North Dakota has about 16,000 people and we’re located right next to a Native American reservation. They have an Indian Health Service (IHS) facility, which is much larger than us though most of our patients are Native American. We also have many of Finnish descent so it’s a farming community mixed with a Native American community. Many are living with co-morbidities and poverty is very real here with many receiving Medicaid.

Population of 1,300 according to U.S. Census 2010 and county seat of Rolette County.

Rex Walk, Phillips County Hospital, CEO: We’re a critical access hospital located about 30 miles south of the Nebraska state line. We do all the normal things you’d expect in a small rural hospital. We have a health clinic, recently started doing respiratory services and have geared our surgical program back up.

The community at one point was split on its support of the hospital so we’ve really spent a lot of time on developing community support because that’s obviously important in rural America. We don’t want to just be an average, ordinary, small rural critical access hospital. I came here for two weeks until they could find an interim CEO and then they ran into some issues with that. I said I would stay two months and now, I’m going on three and a half years. I spent most of my career in community hospitals, worked for a system and large GPO before coming to Phillips County Hospital in Kansas. Here, the town has about 2,500 people and the county just 5,000. We are very rural and very small but the issues we face affect a wide range of age groups and disease states.

Pat Schou, Illinois Critical Access Hospital Network, Executive Director: I’m a nurse by training and background and have held roles as a staff nurse and director of nursing assistant administrator. Twenty years ago, I focused my attention on public health and set up the critical access hospital program here in Illinois. This network helps support our rural hospitals by providing resources, education and training. More and more, we are also addressing patient safety, patient satisfaction and helping members learn how to save their dollars by using their resources more effectively. We started with 20 hospitals and have nearly tripled in size. I’m also the current president of the National Rural Health Association.

Newsroom: What went through your mind when you first started hearing about COVID-19?

Rex Walk: I immediately thought about responsibility and knowing the facts. There were so many initial reports about what was going on in China, which caused a lot of fear. Then, you heard other reports about how this wouldn’t be any worse than the flu. For us, we decided to take a fact-based approach. We were also some of the first in our region to launch community meetings to tie county health leaders and EMS all together. We needed to assure everyone this was not just a big city problem and that we were on top of it. With so much information out there, what’s the right road between hoax and hysteria? As of today, we’ve only had two confirmed cases here. You have to hope for the best and prepare for the worst.

Chris Albertson: A large contingent of the population here has multiple comorbidities like diabetes and high blood pressure. After learning more about COVID-19, you start doing the math and it becomes very scary in a quick hurry. Even at 1%, 1% of 16,000 people is quite a big chunk of the population that you’re going to have to bury potentially. So early on, it was critical to pay attention to it even here in Rolla, North Dakota. I next thought about how we would handle a patient surge and the extra manpower we’d need. We cut back on our visits by about a third and kept it mainly for urgent needs involving infections or mental health. We added housekeeping and laundry staff to keep things as absolutely clean as possible. I also renewed my respiratory therapy license in case we needed more clinicians on the ready.

Newsroom: Let’s talk about positive coronavirus cases. Experts say many cities have hit their peak and rural America is now feeling a surge. In fact, recent reports have come out about outbreaks at meat processing plants, which are often in small towns. How would you rate rural America’s preparedness for this and how have you been impacted?

Population of 7,600 according to U.S. Census 2010. Also home to the Lovejoy Homestead, a former station on the Underground Railroad.

Pat Schou: If I had to put in on a scale from one to 10, rural America was at about a five. Yes, all areas of healthcare across the continuum should be prepared for emergencies but we really didn’t understand the true impact of it – the insult of a pandemic. Today though, we’re probably at a nine because we’ve seen what’s happened in communities across the globe and it’s forced all of us to really think through the process. We’re doing social distancing. We’re more knowledgeable about personal protective equipment (PPE). And, we’ve had our eyes opened about supply chain. Many facilities are now thinking about how to make patients feel safe again once we can re-open for surgery. As someone who lives and works in rural, I see the value of maintaining the rural infrastructure. That’s really critical as we look to the future. Healthcare is tied to everything – no matter where you live. If you are injured at a meat packing plant or on a farm, people don’t want to have to travel two hours for care. Many also travel through our towns and vacation there. The attention to rural must be ongoing – not just during a pandemic. It can only help us to understand and anticipate the resources we need.

Chris Albertson: For those of us in rural communities, there are way more patients than there are doctors and nurses to provide care. Health systems around the globe were caught off guard – nobody was ready for this. We’re already stretched thin and trying to do the most efficient things possible. We need to do more than just get through this. How do you ramp up staffing, PPE, medications, and have the money to do it all at the same time? Could there be a liquidity crisis for healthcare? All of this plays into preparedness and the future. So far, we’ve had nobody hospitalized but a handful of positive cases in the community. We can’t let our guard down and are doing everything we can to remain vigilant.

Newsroom: How vital is the hospital in rural America and why?

Rex Walk: We are friends and neighbors taking care of friends and neighbors – that’s a strategic advantage. Although we are a small organization, bigger isn’t always better. We should be more agile and able to adjust and adapt to the health needs of our evolving community. We just have to make sure that it’s market driven and cost justifiable. Because when you think of it, nearly everything that happens in your community somehow relates to the hospital and delivery of services. If you don’t have a financially sound organization, that can affect the psyche of the community. Think about the hundreds of hospitals at risk of closing and the potential impact on the community and economic development.

Population of 2,500 according to U.S. Census 2010. Also the county seat and largest city in Phillips County.

When we bring businesses in to look things over or recruit teachers and other professionals, one of the first things they ask about is healthcare. There’s also geography. Our community shouldn’t have to drive miles and miles away for high quality care. We have skilled experts right here among us. If we lose sight of that, it could cost an organization dearly. You also need the right partners, especially in times of crisis to make sure you have the right information and products to serve your patients. We were grateful for continued communication, even in the midst of uncertainty.

Chris Albertson: Let’s say Presentation Medical Center wasn’t here. We have four high schools in our area. If something bad happened to any one of those teachers and they weren’t eligible to go to IHS facility, they’ve got a 50 mile ride for their heart attack. Who’s going to live in a place like that? Think about it – you call an ambulance and this hospital isn’t here, you’ve got to ride roughly an hour somewhere to get stabilizing care, only to be transferred to a higher level of care to get your stent or your bypass. You wouldn’t be able to recruit teachers or other employees to work at any other business. When you look at towns that have lost hospitals, the talent and towns are decimated.

My town blows away if we’re not here.

Pat Schou: Rural America accounts for about 20% of the population but covers about 80 to 85% of the geography. That alone presents an access challenge. We see communities made up of the elderly, those with chronic diseases and the reality of poverty. A recent statistic noted one if four children living in rural communities is poor. When you think of all the different societal and clinical needs, we really need greater understanding of our patient unlike ever before so we can take care of our population. How can we change and deliver better care in our population, and in a cost effective way? You can’t overlook 20% of the country. Our needs are changing and we still need resources to keep our rural communities strong. While many received some immediate relief from the government, we’re also still dealing with the reality of limited cash on hand. We’re not talking about billions of dollars in a treasure chest. Some hospitals may have 200 days cash on hand. For nearly half of rural hospitals, they’re likely working with 90 days or less cash on hand.

Newsroom: What advice would you give to other rural healthcare leaders about care during this pandemic and being able to survive it?

Pat Schou: The pandemic affected healthcare everywhere, not just urban areas. We had to furlough people. If you were weren’t needed or reassigned, you still had to say in readiness form because you could have an outbreak in a jail or nursing home. You had to stay in readiness and pay for readiness, through things like training, resources and having the right equipment. So when we think about the future post-COVID-19, it really centers on reimbursement. Rural also has the opportunity to truly take the lead on innovation and access – just look at telehealth. We have to rethink our business. We have to have more partnerships. Maybe we partner with the Walmarts and the Walgreens of the world for more testing services. Maybe we integrate more with home health services or find creative ways to be a more mobile society. If an elderly person lives alone, can we arrange for them to go to assisted living where somebody can monitor them overnight instead of going home alone and having a complication? We can be strong and innovative by being partners in healthcare delivery.

Rex Walk: COVID-19 has drained emotions, efforts and planning. Despite all of that, you must stay focused on leading your organization. Smaller hospitals can sometimes fall into a ‘cultural inferiority complex’ that bigger is better. Quite frankly, it doesn’t have to necessarily be that way. If you listen closely to the needs of the community to develop market-driven solutions, it can lead to long-term success. When I first got here, 90% of the younger people were going elsewhere for services. While we don’t deliver babies, we can offer pediatric services so people don’t have to go outside our town for care. Now, we are able to serve the entire community and not just a segment, while being flexible enough to respond to what we need when we need it.

Get the latest updates on access to high-demand supplies and crisis response resources.

Medline Newsroom Staff

Medline Newsroom Staff

Medline's newsroom staff researches and reports on the latest news and trends in healthcare.